Spratly Islands

| Disputed islands Other names: see below |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Geography | |

| Location | South China Sea |

| Coordinates | (Spratly Island) |

| Total islands | over 750 |

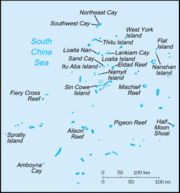

| Major islands | Itu Aba Island Namyit Island Northeast Cay Sin Cowe Island Southwest Cay Spratly Island Swallow Reef Thitu Island West York Island |

| Area | less than 5 square kilometres (1.9 sq mi) |

| Coastline | 926 kilometres (575 mi) |

| Highest point | unnamed location on Southwest Cay 4 metres (13 ft) |

| Administered by | |

| Claimed by | |

| EEZ | Louisa Reef |

| State | Sabah |

| Municipality | Kalayaan, Palawan |

| County | Paracels, Spratlys, and Zhongsha Islands Authority, Hainan |

| Municipality | Kaohsiung |

| Province | Khanh Hoa |

| Demographics | |

| Population | No indigenous population[1] |

| Spratly Islands | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 南沙群島 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 南沙群岛 | ||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

| Filipino name | |||||||||||

| Tagalog | Kapuluan ng Kalayaan | ||||||||||

| Malay name | |||||||||||

| Malay | Kepulauan Spratly | ||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||

| Quốc ngữ | Quần Đảo Trường Sa | ||||||||||

| Hán tự | 群島長沙 | ||||||||||

The Spratly Islands are a group of more than 750 reefs,[2] islets, atolls, cays, and islands in the South China Sea between the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, Vietnam, and China. They comprise less than four square kilometers of land area, spread over more than 425,000 square kilometers of sea. The Spratlys are part of the three archipelagos of the South China Sea, comprising more than 30,000 islands and reefs which so complicates geography, governance and economics in that region of Southeast Asia. Such small and remote islands have little economic value in themselves, but are important in establishing international boundaries. There are no native islanders but there are rich fishing grounds and initial surveys indicate the islands may be near significant oil and gas deposits.

About 45 islands are occupied by relatively small numbers of military forces from the People's Republic of China, the Republic of China (Taiwan), Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam. Brunei has claimed an EEZ in the southeastern part of the Spratlys encompassing just one area of small islands above mean high water (on Louisa Reef.)

Contents |

Geographic and economic overview

- Coordinates:

- Area (land): less than 5 km²

- note: includes 148 or so islets, coral reefs, and seamounts scattered over an area of nearly 410,000 km² of the central South China Sea

- Coastline: 926 km

- Political divisions:

- Brunei: Claims Louisa Reef itself, as well as an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) around that and neighboring reefs [3];

- Malaysia: Part of the state of Sabah (also claimed by the Philippines);

- Philippines: Part of Palawan province;

- People's Republic of China: Part of the Paracels, Spratlys, and Zhongsha Islands Authority, Hainan province;

- Republic of China: Part of Kaohsiung municipality

- Vietnam: Part of Khanh Hoa Province;

- Climate: tropical

- Terrain: flat

- Elevation extremes:

- lowest point: South China Sea (0 m)

- highest point: unnamed location on Southwest Cay (4 m)

- Natural hazards: serious maritime hazards because of numerous banks, reefs and shoals

The islands are most likely volcanic in origin.[4] The islands themselves contain almost no significant arable land and have no indigenous inhabitants, although twenty of the islands, including Itu Aba, the largest, are considered to be able to sustain human life. Natural resources include fish, guano palm, undetermined oil and natural gas potential. Economic activity includes commercial fishing, shipping, and tourism. The proximity to nearby oil- and gas-producing sedimentary basins suggests the potential for oil and gas deposits, but the region is largely unexplored, and there are no reliable estimates of potential reserves. Commercial exploitation of hydrocarbons has yet to be developed. The Spratly Islands have at least three fishing ports, several docks and harbors, at least three heliports, at least four territorial rigging style outposts (especially due west of Namyit)[5], and six to eight airstrips. These islands are strategically located near several primary shipping lanes.

Ecology

Coral reefs

Coral reefs are the predominant structure of these islands; the Spratly group contains over 600 coral reefs in total.[2]

Vegetation

Little vegetation grows on these islands, which are subject to intense monsoons.[2] Larger islands are capable of supporting tropical forest, scrub forest, coastal scrub and grasses.[2] It is difficult to determine which species have been introduced or cultivated by humans.[2] Itu Aba Island was reportedly covered with shrubs, coconut, and mangroves in 1938; pineapple was also cultivated here when it was profitable.[2] Other accounts mention papaya, banana, palm, and even white peach trees growing on one island.[2] A few islands which have been developed as small tourist resorts have had soil and trees brought in and planted where there were none.[2]

Wildlife

The islands that do have vegetation provide important habitats for many seabirds and sea turtles.[2]

Both the Green Turtle (Chelonia mydas, endangered) and the Hawksbill Turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata, critically endangered) formerly occurred in numbers sufficient to support commercial exploitation.[2] These species reportedly continue to nest even on islands inhabited by military personnel (such as Pratas) to some extent, though it is believed that their numbers have declined.[2]

Seabirds use the islands for resting, breeding, and wintering sites.[2] Species found here include Streaked Shearwater (Calonectris Leucomelas), Brown Booby (Sula Leucogaster), Red-Footed Booby (S. sula), Great Crested Tern (Sterna bergii), and White Tern (Gygis Alba).[2] Little information is available regarding current status of the islands’ seabird populations, though it is likely that birds may divert nesting site to smaller, less disturbed islands. Bird eggs cover the majority of Song Tu, a small island in the eastern Danger Zone.[2]

Unfortunately, this ecoregion is still largely a mystery.[2] Scientists have focused their research on the marine environment, while the ecology of the terrestrial environment remains relatively unknown.[2]

Ecological hazards

Political instability, tourism and the increasing industrialization of neighboring countries has led to serious disruption of native flora and fauna, over-exploitation of natural resources, and environmental pollution.[2] Disruption of nesting areas by human activity or by introduced animals, such as dogs, has reduced the number of turtles nesting on the islands.[2] Sea turtles are also slaughtered for food on a significant scale.[2] The sea turtle is a symbol of longevity in Chinese customs and at times the military personnel are given orders to protect the turtles.[2]

Heavy commercial fishing in the region causes other problems. Though outlawed, fishing methods continue to include the use of bottom trawls fitted with chain rollers.[2] In addition, during a recent routine patrol, more than 200 kg of potassium cyanide solution was confiscated from fishermen who had been using it for fish poisoning. These activities have a devastating impact on local marine organisms and coral reefs.[2]

Some interest has been taken in regard to conservation of these island ecosystems.[2] J.W. McManus has explored the possibilities of designating portions of the Spratly Islands as a marine park.[2] One region of the Spratly Archipelago, called Truong Sa, was proposed by Vietnam's Ministry of Science, Technology and the Environment (MOSTE) as a future protected area.[2] The 160 km2 site is currently managed by the Khanh Hoa Provincial People's Committee of Vietnam.[2]

Military groups in the Spratlys have engaged in environmentally damaging activities such as shooting turtles and seabirds, raiding nests, and fishing with explosives.[2] The collection of rare medicinal plants, collecting of wood and hunting for the wildlife trade are common threats to the biodiversity of the entire region, including these islands.[2] Coral habitats are threatened by pollution, over-exploitation of fish and invertebrates, and the use of explosives and poisons as fishing techniques.[2]

History

Early cartography of the Spratly Islands

The first possible human interaction with the Spratly Islands dates back between 600 BCE to 3 BCE. This is based on the theoretical migration patterns of the people of Nanyue (southern China and northern Vietnam) and Old Champa kingdom who may have migrated from Borneo, which may have led them through the Spratly Islands.[6]

Ancient Chinese maps record the "Thousand Li Stretch of Sands"; Qianli Changsha (千里長沙) and the "Ten-Thousand Li of Stone Pools"; Wanli Shitang (萬里石塘)[7], which China today claims refers to the Spratly Islands. The Wanli Shitang have been explored by the Chinese since the Yuan Dynasty and may have been considered within their national boundaries. [8][9] They are also referenced in the 13th century,[10] followed by the Ming Dynasty.[11] When the Ming Dynasty collapsed, the Qing Dynasty continued to include the territory in maps compiled in 1724,[12] 1755,[13] 1767,[14] 1810,[15] and 1817[16]. A Vietnamese map from 1834 also includes the Spratly Islands clumped in with the Paracels (a common occurrence on maps of that time) labeled as "Wanli Changsha".[17]

According to Hanoi, old Vietnamese maps record Bãi Cát Vàng (Golden Sandbanks, referring to both Paracels and the Spratly Islands) which lay near the Coast of the central Vietnam as early as 1838.[18] In Phủ Biên Tạp Lục (Frontier Chronicles) by the scholar Lê Quý Đôn, Hoàng Sa and Trường Sa were defined as belonging to Quảng Ngãi District. He described it as where sea products and shipwrecked cargoes were available to be collected. Vietnamese text written in the 17th century referenced government-sponsored economic activities during the Lê Dynasty, 200 years earlier. The Vietnamese government conducted several geographical surveys of the islands in the 18th century.[18]

Despite the fact that China and Vietnam both made a claim to these territories simultaneously, at the time, neither side was aware that their neighbor had already charted and made claims to the same stretch of islands.[18]

The islands were sporadically visited throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries by mariners from different European powers (including Richard Spratly, after whom the island group derives its most recognizable English name).[19] However, these nations showed little interest in the islands. In 1883, German boats surveyed the Spratly and Paracel Islands but withdrew the survey eventually after receiving protests from the Nguyễn Dynasty. Many European maps before the 20th century do not even make mention of this region.[20]

Military conflict

In 1933, France reasserted its claims from 1887[21] to the Spratly and Paracel Islands on behalf of its then-colony Vietnam.[22] It occupied a number of the Spratly Islands, including Itu Aba, built weather stations on two, and administered them as part of French Indochina. This occupation was protested by the Republic of China government because France admitted finding Chinese fishermen there when French war ships visited the nine islands.[23] In 1935, the ROC government also announced a sovereignty claim on the Spratly Islands. Japan occupied some of the islands in 1939 during World War II, and used the islands as a submarine base for the occupation of Southeast Asia. During the occupation, these islands were called Shinnan Shoto (新南諸島), literally the New Southern Islands, and put under the governance of Taiwan together with the Paracel Islands (西沙群岛). Today, Itu Aba Island is still administrated by the Republic of China, which took over the control of Taiwan from Japan in 1945.

Following the defeat of Japan at the end of World War II, China re-claimed the entirety of the Spratly Islands (including Itu Aba), accepting the Japanese surrender on the islands based on the Cairo and Potsdam Declarations. The ROC government withdrew from most of the Spratly and Paracel Islands after they retreated to Taiwan from the opposing Communist Party of China, which founded the People's Republic of China in 1949.[24] ROC quietly withdrew troops from Itu Aba in 1950, but reinstated them in 1956 in response to Tomas Cloma's sudden claim to the island as part of Freedomland.[25]

Japan renounced all claims to the islands in the 1951 San Francisco Peace Treaty, together with the Paracels, Pratas & other islands captured from China, upon which China reasserted its claim to the islands.

The naval units of the Vietnamese government took over in Trường Sa after the defeat of the French at the end of the First Indochina War. In 1958, the People's Republic of China issued a declaration defining its territorial waters, which encompassed the Spratly Islands. North Vietnam's prime minister, Phạm Văn Đồng, sent a formal note to Zhou Enlai, stating that the Government of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam respects the decision by China regarding the 12 nautical mile limit of territorial waters [26]. However, South Vietnam still claimed jurisdiction over the islands.

Amateur radio

The International Telecommunications Union issues distinct call sign prefixes for use by national bodies. Operators on one of the Spratly Islands would normally use a call sign issued by the country claiming that island. However, the non-ITU allocated prefix of 1S has sometimes been used to identify an amateur operating there.[27]

References and notes

- ↑ Note: There are scattered garrisons occupied by personnel of several claimant states.CIA World Factbook : Spratley Islands

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 2.22 2.23 2.24 2.25 2.26 2.27 2.28 World Wild Life: Terrestrial Ecoregions -- South China Sea Islands, World Lildlife Fund.

- ↑ Borneo Post: When All Else Fails Additionally, pages 48 and 51 of "The Brunei-Malaysia Dispute over Territorial and Maritime Claims in International Law" by R. Haller-Trost, Clive Schofield, and Martin Pratt, published by the International Boundaries Research Unit, University of Durham, UK, points out that this is, in fact, a "territorial dispute" between Brunei and other claimants over the ownership of one above-water feature (Louisa Reef)

- ↑ MARA C. HURWITT, U.S. STRATEGY IN SOUTHEAST ASIA: THE SPRATLY ISLANDS DISPUTE (Masters Thesis), Defense Technical Information center.

- ↑ A Chinese Outpost.

- ↑ Thurgood, Graham (1999). From Ancient Cham to Modern Dialects: Two Thousand Years of Language Contact and Change. University of Hawaii Press. p. 16. ISBN 9780824821319. http://books.google.com/?id=MBGYb84A7SAC..

- ↑ Image: General Map of Distances and Historic Capitals, Wikimedia Commons.

- ↑ Jianming Shen (1996). "Territorial Aspects of the South China Sea Island Disputes". In Nordquist, Myron H.; Moore, John Norton. Security Flashpoints. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 165–166. http://books.google.com/?id=DKXRRfWtkw8C&pg=PA163&lpg=PA163&dq=%22wang+dayuan%22+spratly., ISBN 90-411-1056-9 ISBN 978-90-411-1056-5.

- ↑ Historical Evidence To Support China's Sovereignty over Nansha Islands

- ↑ 《元史》地理志;《元代疆域图叙》

- ↑ 《海南卫指挥佥事柴公墓志铬》

- ↑ 《清直省分图》天下总舆图

- ↑ 皇清各直省分图》之《天下总舆图

- ↑ 《大清万年一统天下全图》

- ↑ 《大清万年一统地量全图》

- ↑ 《大清一统天下全图》

- ↑ Alleged Early Map of the Spratly Islands near the Vietnamese Coast

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 King C. Chen, China's War with Vietnam (1979) pp.43-44.

- ↑ MARITIME BRIEFING, Volume I, Number 6: A Geographical Description of the Spratly Island and an Account of Hydrographic Surveys Amongst Those Islands, 1995 by David Hancox and Victor Prescott. Pages 14–15

- ↑ Map of Asia 1892, University of Texas

- ↑ Paracel Islands, worldstatesmen.org

- ↑ Spratly Islands, Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2008. All Rights Reserved.

- ↑ Todd C. Kelly, Vietnamese Claims to the Truong Sa Archipelago, Explorations in Southeast Asian Studies, Vol.3, Fall 1999.

- ↑ Spratly Islands, MSN encarta.

- ↑ Kivimäki, Timo (2002), War Or Peace in the South China Sea?, Nordic Institute of Asian Studies (NIAS), ISBN 87-91114-01-2

- ↑ PRC's declaration over the islands in 1958 Xinhua archives

- ↑ Numbered call sign prefixes from RAC

Other sources

- Spick, Mike. Dangerous Ground!, Air Forces Monthly, December 1993

See also

- Spratly Islands dispute

- Kingdom of Humanity

- South China Sea Islands

- Paracel Islands

- Junk Keying

- Policies, activities and history of the Philippines in Spratly Islands

- Mutual Defense Treaty (U.S.–Philippines)

- Kalayaan, Palawan, Philippines

- Zheng He

- Crysis, a computer game set on the Spratly Islands.

- SSN, a computer game set during a conflict over the Spratly Islands.

- List of islands in the South China Sea

- Rockall

External links

- Spratly Islands travel guide from Wikitravel

- Satellite images of all islands and reefs of the Spratly Islands.

- List of atolls with areas

- Flags of the World (FOTW) entry with various micronations on the Spratly Islands.

- Map showing the claims

- A tabular summary about the Spratly and Paracel Islands

- Another overview table of the Spratly Islands

- CIA World Factbook for Spratly Islands

- Some coordinate points of reefs

- Google Map of Spratly Islands

- Wikimedia Atlas of the Spratly Islands

|

||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||